- July 22, 2019

- Data Visualization

If you are reading this and live in the US, it is likely you spend about 42 hours per year stuck in traffic. If you live in cities like Los Angeles and commute every day (and I pray for you if you do), its likely you spend twice that amount of time in gridlock. It is also quite likely that you have your own car and drive alone to work, as do 76 percent of all workers. The map below from CityLab shows where the greatest percentage of commuters drive alone to work.

This obsession with individual car ownership and the tendency to commute alone has created the traffic problem that everyone claims to hate. More than just a nuisance, traffic has taken from us our time and money, and has destroyed our environment and personal health.

With all those hours spent sitting in traffic jams, the American economy is hurting. A 2017 study conducted by transportation consulting firm, INRIX, found that traffic congestion cost the US economy $305 billion in 2017 alone. Beyond that, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), transportation is responsible for nearly 30 percent of greenhouse gases emitted in the US. These emissions create air pollution, which nine out of 10 of us breathe every single day and is responsible for the deaths of seven million people each year.

Despite the challenges associated with traffic congestion and the damage being done to individual citizens and the economy, studies show that changing commuting habits is notoriously difficult. So, what are cities doing to try and address this growing congestion problem?

Cities are going to great lengths to reduce traffic congestion and individual car use

Cities across the world are taking great measures to curb traffic congestion and reduce individual car use. Their strategies span across technology and incentives.

Some technology solutions for reducing traffic congestion include:

-

Smart traffic lights that adapt to changing patterns in real time

-

Vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) smart corridors where sensors monitor traffic conditions ahead and send alerts directly to drivers, and

-

Electronic tolling that streamlines toll collection by scanning license plates and collecting fees directly from driver’s online accounts

Incentives that cities are using to alleviate traffic include:

-

Free public transit to attract more riders

-

Congestion pricing where drivers pay higher fees to drive on high-traffic roadways during peak hours, and

-

High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes where only vehicles that have a minimum of two or three passengers are allowed to travel on high-traffic roadways

Despite these great efforts, traffic seems to only be getting worse and emission levels are higher than ever. Some cities are taking a step back from these new innovative solutions to get as low tech as possible: ban cars altogether.

Cities across the world are slowly starting to ban cars altogether

While the list of cities experimenting with car bans is increasing, a few notable cases include:

-

Madrid – The city’s government officially banned all non-resident vehicles from its city center in November 2018. The only vehicles allowed will be those “that belong to residents who live there, zero emissions delivery vehicles, taxis, and public transit.” This ban came as part of the national government’s Law on Climate Change and Energy Transition which lays out broader plans to prohibit “all but zero emissions vehicles” from the city centers of all municipalities with a populations greater than 50,000 by 2025 (138 cities across the country).

-

Paris – Mayor Anne Hidalgo established rules stating that cars made prior to 1997 are banned from the city center on weekdays. She also laid out plans to make select streets available only to electric vehicles by 2020 and declared the city’s “urban core” care-free on the first Sunday of every month.

-

Oslo – The city has begun to scale back the availability of street parking spaces and has banned cars from several streets in its city center. Similarly, Amsterdam has announced a more ambitious plan to strategically eliminate 11,200 parking spaces by 2025.

These models and similar iterations have been tried in many other cities across the world and are beginning to prove successful. New York City saw increases in retail activity after establishing “pedestrian plazas” on some of the city’s busiest streets. Likewise, after Philadelphia eliminated some street parking, the city also saw a boost in sales for businesses where street parking was eliminated. Following Oslo’s city center car ban and reduction in street parking, the city saw a 10 percent jump in the number of pedestrians visiting the city center than the year prior.

While the idea of car-free living in cities seems promising, the concept has understandably been met with public backlash in many of the cities where these plans have been introduced. Nonetheless, the current state of traffic congestion is unsustainable and will only continue to hurt humans, the economy, and the environment if more is not done to eliminate it.

The remainder of this article will discuss how the City of Atlanta is leveraging maps and data to initiate discussion with residents and identify areas most suitable for car-free living.

Atlanta’s data-driven, map-based framework for advancing plans for a car-free future

In 2017, Atlanta’s City Planning Department released The Atlanta City Design: Aspiring to the Beloved Community, a “guiding document” created to “articulate an aspiration for the future city that Atlantans can fall in love with... and transform Atlanta into the best possible version of itself.” An important piece of The Atlanta City Design is “Atlanta’s Transportation Plan” (ATP), a comprehensive planning document designed with the goal in mind of “building a transportation network that reduces automobile reliance and offers alternative travel solutions that are convenient, affordable and safe.”

The ATP was created in an anticipation of a jump in the city’s population from 500,000 today, to 1.3 million in the coming decades. The plan proposes a series of progressive steps the city must take to transform its transportation network to support this population growth, reduce car reliance and alleviate traffic congestion. Atlantans currently drive far more and use public transportation far less than residents in similar cities like Washington, D.C., Seattle, and Chicago. To put numbers into perspective, public transportation ridership in Atlanta is about 10 percent compared to anywhere from 20 to 38 percent in the peer cities mentioned.

Car-free living is the key to the long-term vision of the ATP because Atlantans already spend more time commuting than residents of any other major city in the country besides New York and Los Angeles. Additionally, there is extremely limited room to expand road capacity in the city. With so many residents owning their own car, current infrastructure will not be able to support a near three times increase in the population in the coming decades.

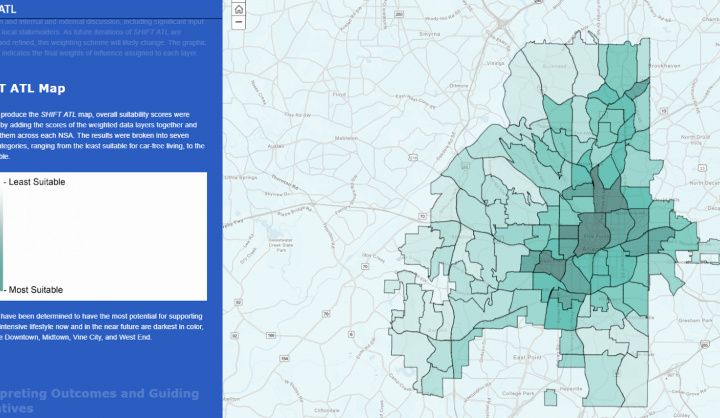

City leaders in Atlanta recognized that drastic change will not occur without the public’s full participation in the transformation and they understood that would not be possible without a wide-spread cultural and behavioral change. To spark a conversation with residents and provide a data-driven framework for evaluating progress towards car-free livability, the city created SHIFT ATL, an analysis of Atlanta neighborhoods that scored each “based on how suitable they are for living a less car-dependent lifestyle.” The map uses the Atlanta Regional Commission’s 102 Neighborhood Statistical Areas (NSAs), which were well-suited for SHIFT ATL because they have a population of at least 2,000 people, are made up of urban census blocks, and fall mostly within Atlanta’s Neighborhood Planning Units (NPUs).

Using insights from industry experts, significant stakeholder input, and the professional experiences of the SHIFT ATL team which consisted up of members from several city agencies, the plan lays out nine key factors that impact a person’s ability to live a less car-dependent lifestyle:

Layer 1: Walking access to MARTA rail stations

NSAs within one-quarter of a mile, and one-half of a mile walk of a Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) rail station received high points for car-free livability.

Layer 2: Bicycle access to MARTA rail stations

Like walking access above, NSAs within one-half of a mile and a mile bike ride of a MARTA rail stations received points for car-free livability because all MARTA trains allow bikes on board.

Layer 3: Walking access to short headway bus service

For NSAs within a one-quarter mile walk of “short headway” bus service (meaning the wait between buses is no longer than 15 minutes) also received points. There are currently six bus routes throughout Atlanta that meet the short headway standard established for this score.

Layer 4 and 5: Access to groceries

Access to fresh food and groceries is critical to leading a car-free lifestyle. NSAs within a quarter-mile and half-mile walk or bike ride of a grocery store received points as well.

Layer 6: Relay bikeshare coverage area

NSAs within a mile of the relay bikeshare network coverage area, currently the only bikeshare system operating in Atlanta, received points for car-free livability.

Layer 7: Slope

Incredibly important to car-free livability is the degree of slope on city streets. The greater the slope residents have to endure when walking or taking a bike to their destination, the more difficult it is for them to use these alternative modes of transportation. NSAs with the lowest degree of slope received points in the analysis.

Layer 8: Intersection density

The greater the density of intersections in an NSA, the more access area residents have to different destinations in the city, promoting walking and biking as more attractive transportation options.

Layer 9: Variety

Building off intersection density, NSAs near a greater variety of commercial destinations also received high scores. With more things to do close by, NSAs with more variety make car-free living easier.

To give weight to each data point in the analysis and rank NSAs on a scale from least to most suitable for car-free living, the SHIFT ATL team conducted several different analyses and engaged in debate with critical stakeholders. In the end, they decided on the following breakdown:

Using these weightings, the team then layered each data point on top of a map, added up their weighted scores, and averaged them out across the NSA, producing the following map. The darkest shaded NSAs were considered most suitable, while the lightest were considered least suitable.

The SHIFT ATL team recognizes that the nine data layers used for this analysis may not be the only, or the even the best, layers to use to make decisions about projects or policies that hope to advance the city’s vision of a car free future. They have acknowledged that this is just the beginning of a long-term discussion about what the city will look like in the coming decades. In the short term, these maps and weighted scores will be used to focus densification, multimodal transportation, and other mobility initiatives on areas most suitable for car free living first, with the hopes of expanding these efforts to other parts of the city over time. Other parts of the city considered less suitable are where efforts to expand transit networks and bolster development will be focused in the future. The hope here is to give residents in those areas access to commercial activity and public transit that enables them to travel to the city’s urban core without their own vehicle. The city plans to continue the conversation with residents new and old as the population grows, and they will refine their plans as they put SHIFT ATL into action.