- June 12, 2023

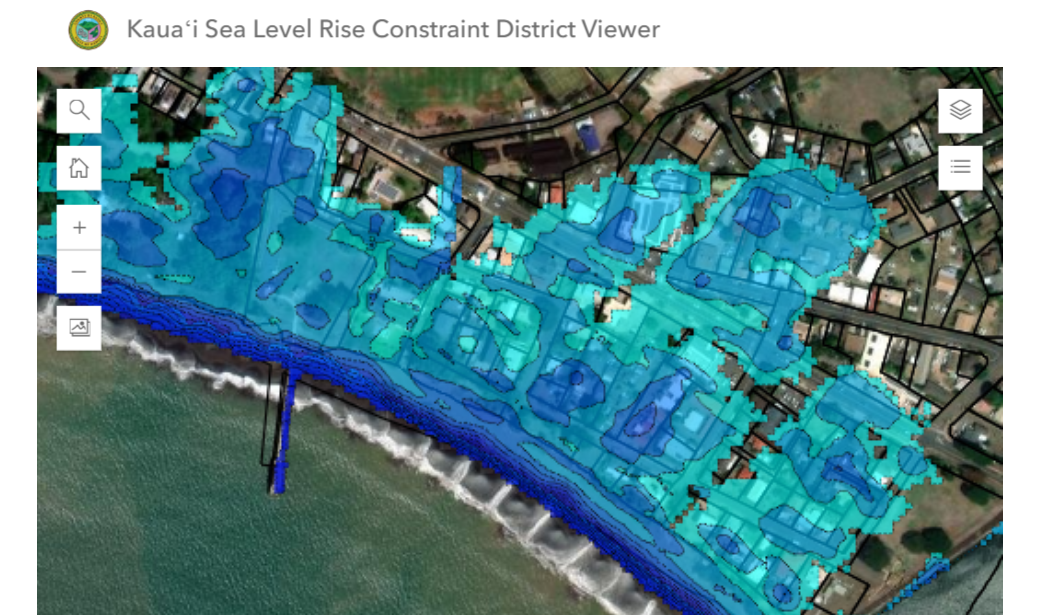

- Data Visualization

First adopted by the Swedish Parliament in 1997, Vision Zero is a collection of strategies whose goal is to eliminate traffic related deaths and serious injuries. Since its implementation in Sweden, the movement has spread across the world. Scores of communities in the United States have adopted Vision Zero plans, some more elaborate than others.

Vision Zero situates responsibility for traffic safety with both road users and road managers. It is a collaborative enterprise, requiring cooperation across municipal, state and federal agencies while relying on community input and participation. Vision Zero initiatives include education/outreach, infrastructure configuration and maintenance, enforcement, and traffic policies such as speed management.

No matter what it is called or how comprehensive the approach to improving traffic safety, effective local action begins with broadly collected and spatially oriented data. In Bethlehem Pennsylvania, public health officials use data visualization and locally gathered intelligence to understand where and how to adjust conditions on the ground to improve outcomes for pedestrians, cyclists and motorists.

In many jurisdictions Vision Zero represents an evolution of road safety programs that have been underway for decades. Bethlehem’s Health Bureau has overseen the city’s highway safety initiatives since 1999, at which time the city convened a diverse group of partners to provide recommendations, coordinate, and generate public support for traffic safety activities. That group, the Citizens Traffic Advisory Committee (CTAC), currently includes representatives from the Health Bureau, the police, Planning Department, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT), community organizations, health networks, and residents. In addition to its charted responsibilities, CTAC now functions as Bethlehem’s Vision Zero committee.

Using a public health lens, Bethlehem focuses on multiple facets of road safety -- pedestrian, bike, motorcycle safety; drunk, aggressive, and impaired driving; and seatbelt, child restraint and behavior-related education campaigns. As Sherri L. Penchishen, director of chronic disease programs and author of Bethlehem’s first Vision Zero plan notes, “When the city heard about Vision Zero in 2014 or 2015, we realized that we were already implementing many of its components. What we lacked was a formalized plan, which we developed in 2016 and updated in 2022.”

For years Bethlehem used a home-grown widget to identify traffic safety hotspots for investigation and remediation. City officials collected data on crashes, injuries and fatalities from police reports, retrieved manually or sent by email to the Health Bureau. Data were visualized geographically--although not in real time. When COVID hit, Bethlehem leaned into the use of location intelligence.

Today police officers enter “reportable” crash, fatality and injury data into TraCS (Traffic and Criminal Software) provided by PennDOT. Police also enter “non-reportable” crash data into TraCS. Bethlehem developed this important enhancement to generate a more robust window into local conditions. Reportable and non-reportable data on motor vehicles, bicycle and pedestrian crashes, fatalities and injuries are now mapped in real time.

Health Bureau staff monitor the data and tag emerging crash, fatality and injury clusters for further investigation. Problem areas are inspected visually, frequently with input from residents and visitors. Recommendations for remediation are shared with the CTAC for feedback. In many cities, as in Bethlehem, this process leads to safety enhancements such as decommissioning bridges, reconfiguring streets, adding edge lines, building bulb-outs and recalibrating traffic lights. Adding non-reportable incidents, which occur with greater frequency, to their maps has allowed transportation employees to identify problem areas more quickly. And in turn, to implement pre-emptive solutions, often at a lower cost.

In addition to police reports, Bethlehem gathers resident and visitor complaint data following much the same process as it does with the TraCS data.

Vision Zero is not without controversy. Some experts believe that its goals are unrealistic. They argue that reducing traffic related fatalities and serious injuries to zero cannot be achieved without the investment of substantial resources and political will. Irrespective of the name given, improving traffic safety requires the participation of a diverse set of stakeholders committed to using a public heath model. For Bethlehem this means broadening the data collected, organizing it spatially all with the goal of reducing crashes, fatalities, and injuries, making streets multi-modal and improving safety for residents and visitors.

Since Bethlehem implemented its Vision Zero initiatives, it has seen a decline in motorcycle, bicycle and pedestrian fatalities as well as a decline in crash severity. Penchishen attributes Bethlehem’s success to multiple factors. “As a public health professional, more and more I see how geographically anchored data (whatever its source) can and should be utilized to drive local decision-making.”

Stephen Goldsmith is the Derek Bok Professor of the Practice of Urban Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and the

Stephen Goldsmith is the Derek Bok Professor of the Practice of Urban Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and the  Kate Markin Coleman has thirty years of experience as a senior executive in the private and social sectors. Her current research, advising and speaking focuses on social sector impact, scaling, cross sector collaboration and workforce development. She directs IAS advising LLC, a strategic consultancy for social ventures. She is co-author of two recently published books, Growing Fairly; How to Build Opportunity and Equity in Workforce Development and Collaborative Cities: Mapping Solutions to Wicked Problems.

Kate Markin Coleman has thirty years of experience as a senior executive in the private and social sectors. Her current research, advising and speaking focuses on social sector impact, scaling, cross sector collaboration and workforce development. She directs IAS advising LLC, a strategic consultancy for social ventures. She is co-author of two recently published books, Growing Fairly; How to Build Opportunity and Equity in Workforce Development and Collaborative Cities: Mapping Solutions to Wicked Problems.