- November 20, 2023

- Housing

As federal moratoriums ended in August 2021, and many cities experienced an increase in evictions along with rising rents, this one-two punch left many renters in even worse positions than before. Compounded by soaring inflation rates, eviction filings have not only returned to pre-pandemic levels but have exceeded them, as reported by the Eviction Lab. Moreover, it's possible that those numbers are still too low, as many tenants will vacate their homes before facing formal eviction.

While the mere threat of eviction can be as detrimental as eviction itself, the negative outcomes of both formal and informal evictions manifest in various ways, from individual and familial instability to broader public health concerns. There is also a distinct racial divide in eviction rates, which disproportionately affects Black women and mothers.

As demonstrated during the pandemic, the federal government has a significant role to play in preventing evictions. However, there are numerous ways in which cities can, and should, collaborate with communities to help residents remain in their homes. This includes partnering with tenants, landlords, utility companies, advocacy groups, state governments, and universities on data-sharing, education, and basic protections.

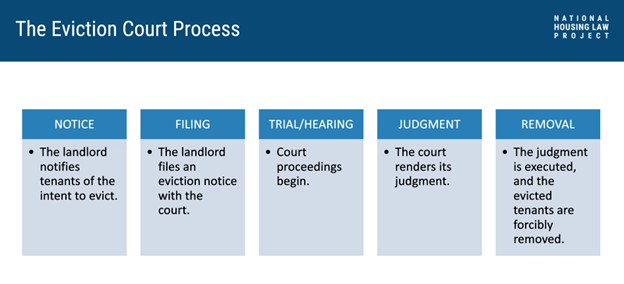

Marie Claire Tran-Leung, the evictions initiative project director at the National Housing Law Project (NHLP), recently presented at the Harvard Kennedy School about the role of local governments. One of the key factors she emphasized is timing; when a city intervenes can have a substantial impact on tenants. She recommended that local officials intervene at the latest in the eviction court process, and ideally before the eviction is officially filed by a landlord. According to Tran-Leung, this not only prevents evictions on records but also alleviates the burden on lawyers working on these cases, many who are volunteers or part of advocacy groups. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, studies have shown that as eviction filing rates go up then rates of homelessness increase.

Yet for many cities, officials are only notified of an eviction during the filing process. There are several ways, outlined below, through which local leaders can become aware of these situations and implement preventative measures before reaching the court, while also providing support to renters undergoing the process to help them stay in their homes.

Early Intervention Points

Opportunity One: Local Data

In Philadelphia, this takes the form of a free, pre-trial Eviction Diversion Program; before landlords can file for eviction, they must go through a mandatory mediation process. The city also implements a “right to counsel” policy, which allows renters, often lacking legal representation, to access lawyers specializing in housing matters. According to City Ordinance #220655, “landlord good faith participation in EDP is required before seeking a legal eviction through court,” which means that negotiation and/or mediation must occur first, with legal action being the last resort. This not only improves outcomes for tenants but also provides the city with information about eviction trends or cases without resorting to court filings.

Another method to identify potential evictions is through data on utility payments, particularly in homes where renters cover bills like water and electricity. In the Preventing Water Shutoffs for Low-Income Households guide from the US Water Alliance, a review of pilots in 10 cities helps uncover essential data to collect. This includes previous shutoffs due to nonpayment or monthly delinquencies, patterns of repeated shutoffs versus one-time occurrences, demographic data disaggregated and overlaid on maps of shutoffs, and enrollment in assistance programs. This data, which helps prevent water shutoffs, can also be shared as potential indicators of issues with paying rent and potential intervention points to prevent evictions.

Opportunity Two: Working with Tenants

City officials often observe a knowledge gap between renters and landlords. Many residents are unaware of their rights or available resources; for instance, some residents, fearing eviction, endure squalor and unsafe conditions instead of speaking up, fearing retaliation. Syracuse has a Rental Registry that requires landlords to register with the city's Division of Code Enforcement and meet compliance with code standards or risk penalties, including fines. In Detroit, renters can call a city hotline to report delinquent landlords to the building inspection team, and tenants have the right to utilize an escrow program that withholds their rent until issues are resolved. Many cities also provide tenants with right to counsel, an important offer; however, decreasing the cases in the first place takes the burden off lawyers and allows them to focus on fewer, more urgent cases.

However, if residents are unaware of these services, many renters will vacate a property as soon as they receive a pre-filing notice of eviction. According to Tran-Leung, individuals who "self-evict" may not understand, for example, that an eviction notice is not an order to leave. As illustrated in the graphic at the beginning of this article, multiple steps are required before renters need to vacate a property. "The city should be taking proactive steps to educate renters about their rights to prevent them from unnecessarily leaving their housing," she said.

Tran-Leung recommends making resources available to not just individual renters but to community-based organizations, as they are “some of the best messengers for accessing help.” She also points out that targeted outreach should focus on the most vulnerable groups, such as undocumented immigrants, as they are the most likely to self-evict in order to avoid court or law enforcement involvement. These community touchpoints are also important sources for qualitative data, which can further inform outreach and prevention work. All of these strategies ensure that the city is aware of conditions that could lead to an eviction or are alerted to potential evictions by residents and community members who see the city as partners.

Opportunity Three: Convening Stakeholders

Engaging landlords and other relevant groups in eviction prevention is crucial; the power of convening stakeholders “is one of the strongest tools that mayors have,” said Tran-Leung. She recommends that city leaders bring together renters, tenant unions, legal and direct service providers for tenants, law enforcement (as they often handle the actual evictions) and landlords that range from small, family landlords to large corporate groups. “Mayors have the benefit of being able to bring in the different sides, to make sure that all voices are heard and to facilitate a problem-solving process, so bring in the whole ecosystem,” said Tran-Leung. Traditionally, the power imbalance between renter and landlord tilts in favor of the latter, so mayors can play an important role in creating a level playing field.

In one West Coast city, where a no-fault eviction ordinance was recently passed, the mayor convened all stakeholders to participate in the discussion. Initially, different groups met separately, but the city incentivized landlords to join the larger discussion by explaining that non-participation would result in them having no say in legislation or decisions. This approach successfully brought together diverse groups and garnered consensus.

In Houston, various segments of the municipal government collaborate to address unsafe or unsanitary conditions. The police, fire, and public health departments can work with the municipal court to levy fines on landlords. If a health concern is identified, representatives from each department can conduct an unannounced coordinated inspection to determine if landlords are evicting people living in poor conditions. Several landlords have been motivated to comply with local health and safety regulations, and the taskforce provides an opportunity to engage key leaders in understanding the situation in multifamily units and sharing data.

Another key stakeholder is the local public housing authorities (PHAs) as they are “important sources of affordable housing and administer the public housing program and also work with landlords participating in the Housing Choice Voucher program,” said Tran-Leung. PHAs can be lost in the discussion about landlord stakeholders, but their practices greatly impact low-income renters. Philadelphia’s eviction prevention task force is an important example, as they developed this infrastructure pre-pandemic and specifically targeted evictions in PHAs which had been higher than the national average.

The rise of corporate landlords in many cities over the past several years has also changed the landscape; many government officials report that these groups are more likely to evict tenants for minor reasons. It also requires city leaders to collaborate with state or federal regulators to address large corporate holdings. In one instance in Chicago, the federal government sued and imposed fines on a corporate landlord that rented multifamily properties in terrible conditions, which the city and renters associations had already tried to have addressed. Public Housing Authorities are also key stakeholders in these conversations, especially as public housing often serves as a last resort for low-income renters.

According to Tran-Leung "good officials combined with very strong advocacy that's grounded in the tenant experiences" will make a significant difference. Any way that mayors can help facilitate a more equitable balance of power between landlords and tenants, provide space for mediation and education, and collect cross-jurisdictional data will make a significant difference in the lives of renters and the overall health of a city.