- October 20, 2015

- Project on Munipical Innovation

Evidence from cities across America shows that racial minorities perform less well on a wide array of indicators—from wealth, to health, to education. In this context, and against the backdrop of increasing attention to racial inequality in cities, members of the Project on Municipal Innovation - Advisory Group came together in September for a session called “Operationalizing Race Equity in City Government.”

Learning from pioneers

Julie Nelson, Director of The Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE), told members that racial inequities are not random: “They were intentionally created over time, and government played a role in doing that.” Addressing race equity concerns thus requires changing policies and shifting the culture of city government. This session highlighted internal management strategies for changing culture, rather than public-facing initiatives, discussing how internal realignment is a necessary first step.

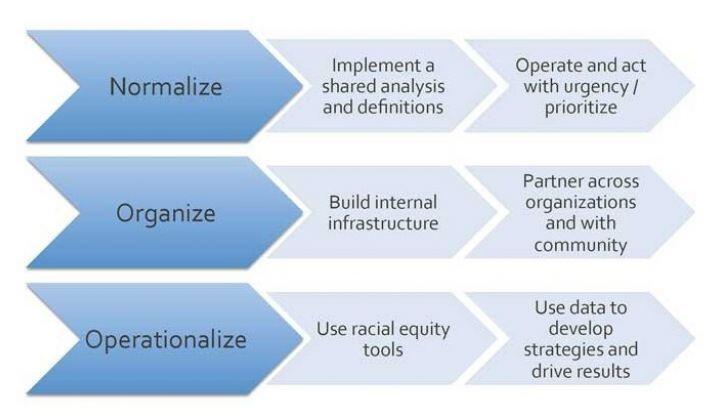

Nelson gave an overview of key strategies that are universally relevant, even as specifics vary according to an individual city’s context:

- Normalize: Use a shared definition of racial equity and institutionalized racism among government staff; Align city staff on a shared sense of urgency/priority

- Organize: Build internal infrastructure to address racial equity issues within government and through partnerships with community

- Operationalize: Implement racial equity tools; Use data to develop strategies and drive results

Greg Nickels, former Mayor of Seattle, was an early pioneer in this work. Working with Nelson, who was then serving as the Director of the Seattle Office of Civil Rights, Nickels created the Race and Social Justice Initiative in 2004 to help advance his race equity agenda. Every city agency was required to examine how their services were being delivered, and whether it could be done more equitably. Nickels and his team emphasized that every budget proposal had to be examined through a race and social justice lens, and every new initiative had to be justified in terms of how it advances those goals. The program also offered formal training on institutional racism to Seattle’s 11,000 city employees, ensuring that they knew its definition and how to combat it.

According to Nickels, “There were many skeptics in city government or people who told me it was just plain stupid politically… but once we figure out how to make it a safe conversation, people embraced it.” Over time, race equity became embedded in the culture of the city government, so much so that Nickels’ successor continued the effort, and 85% of city employees identified it as an important part of their work.

Current promising practices

Next, Kristin Beckmann, Deputy Mayor of St. Paul, shared an account of her city’s efforts to close race equity gaps. She worked closely with Nelson and GARE to adapt the toolkit that had been successful in Seattle to St. Paul. As Beckmann said, “Having a city out in front the way Seattle has been was helpful in bringing people along the change spectrum.” Every department was required to devise a 2015 action plan around racial equity. To ensure buy-in, Beckmann and Nelson worked closely with individual department heads, each of whom was required to identify a single policy to be assessed by the toolkit and workshopped by the team. Already, all directors have undergone a two-day training, and the city expects all 3,000 city employees to go through racial equity training by the end of 2017. In an effort to ensure the sustainability of training, St. Paul has also sought private philanthropy support to bring the capacity to train employees in-house.

Finally, Tomiquia Moss, Chief of Staff of Oakland, California, spoke about her city’s newly-created department of race and equity. The department will examine city policy, hiring processes, and distribution of resources for racial bias, and make recommendations to prevent it. Moss talked about the challenge of building infrastructure to support this work without falling prey to the erroneous assumption that this new department could solve all race issues in Oakland. Moss described how the high levels of racial diversity and history of social movements in Oakland makes conversations about race and racism closer to the forefront of government work: “We’re figuring out how to engage the citizens in that dialogue, and how to translate that into a felt experience of equity,” she said.

In the open discussion following the panel, representatives from a range of cities expressed urgency about and enthusiasm for this work, in addition to worries about backlash and implementation challenges. It is clear that there is important work to be done in city governments looking to translate racial equity goals into actionable modifications to policy and service delivery. It is also clear that this work is challenging, as it forces uncomfortable questions and requires a shift in institutional culture to prioritize a wholly new set of criteria in already complex decision-making processes.